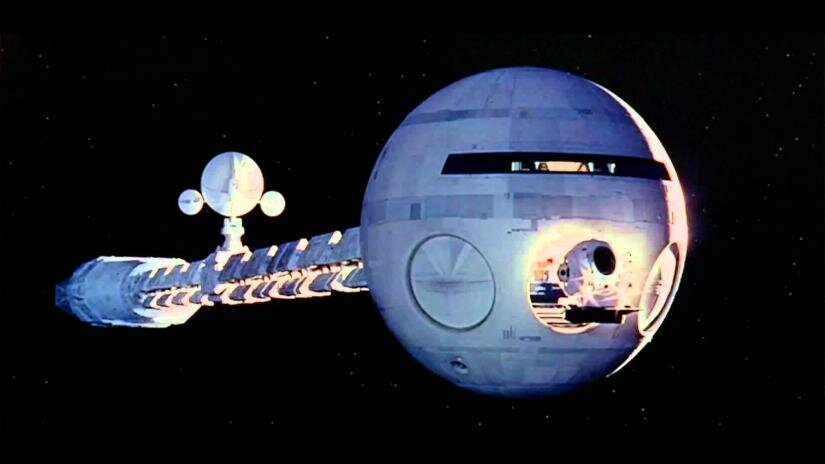

2001 captures the sublime in space

The sublime is a difficult feeling to articulate. Broadly, it’s a mixture of beauty and terror. It’s a sensation of beauty that has nothing to be with prettiness. The sublime is not found in cuteness or quaintness, but in scenes that inspire awe and wonder. It’s a beauty that is hard to look at, even hard to comprehend, but also hard to turn away from.

What is the sublime?

The 18th-century clergyman and Whig politician Edmund Burke , who has the dubious honour of being the founder of modern conservatism, said that: “No passion effectually robs the mind of all its powers of acting and reasoning as terror. And whatever is terrible in refuse to sight is sublime.” Burke believed that the sublime and beauty were mutually exclusive. He found the sublime in the poetry of John Milton, but not in the paintings of his day.

For a more modern commentary on the sublime, we need to look to Jonathan Meades, writer, documentary filmmaker, surrealist artist and the former Times restaurant critic. Meades said that: “The witness to the sublime is overwhelmed by vastness, by awe, by wonder, by terror. The sublime is crushing.”

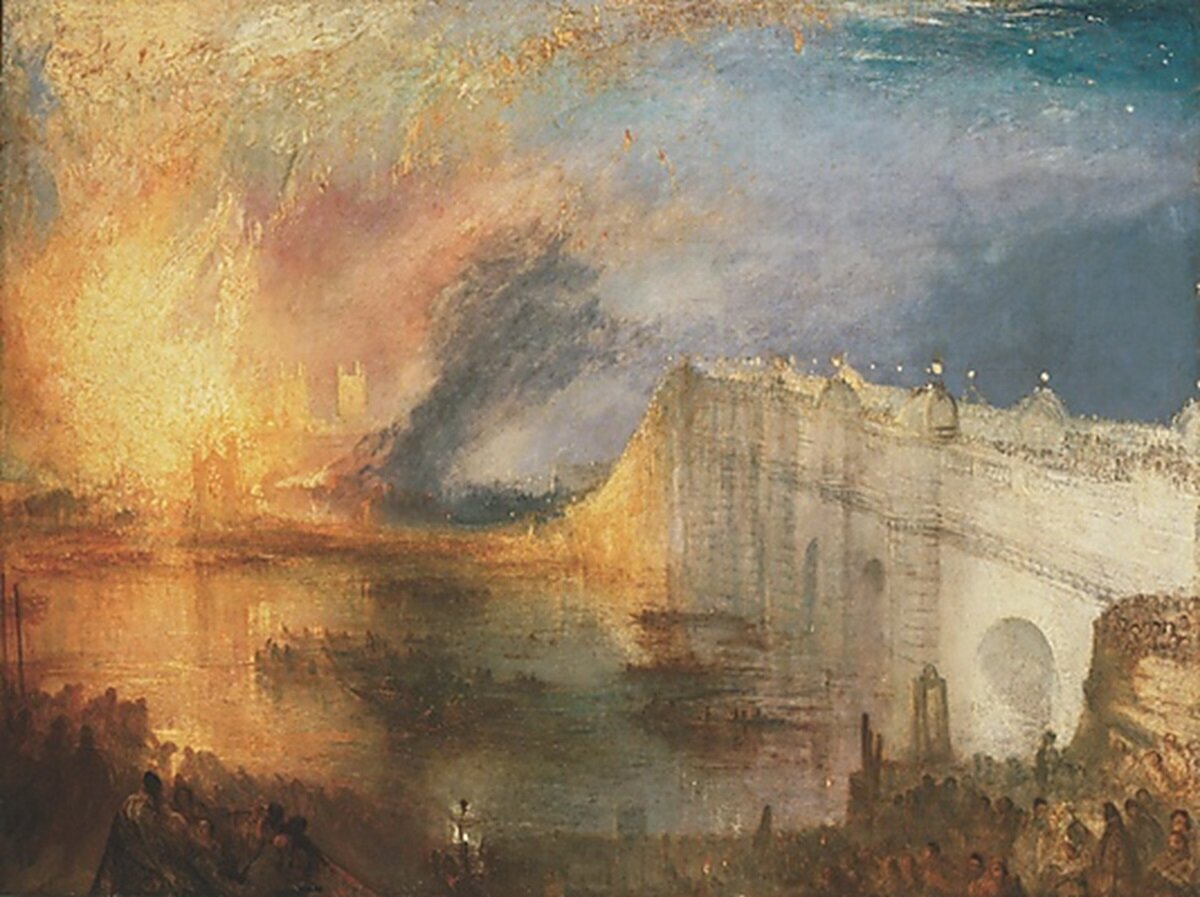

Meades identified the sublime with nature in seething oceans, basalt columns, waterfalls and the screaming wind. “Forces beyond human control”. He also identified the sublime with the painting of J. M. W. Turner, Caspar David Friedrich and John Martin, the latter of which he said his: “Every waking day was a molten apocalypse.”

Meades makes a crucial distinction that: “Paintings which attempt to capture the sublime are not themselves sublime. Maybe any form of representation precludes sensation of sublimity.” He identified the sublime more with architecture. Not with a particular architecture movement or style, but with military installations, pylons, dams, oil refineries, power stations and gigantic chimneys. These structures challenge the forces of nature. Meades said: “Mankind usurped god. Mankind has, to put it mildly, augmented the inventory of the sublime, not through literary or pictorial representation, not by making art about it, but by matching it.”

I would add to Meades’s list that the sublime can be found in the painting of Mark Rothko - especially his composition for the Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building on Park Avenue, New York, which is now resident in the Tate Modern - and in the films of Nicolas Winding Refen. The sensation of beauty mixed with terror can be directly experienced through the strange, artful delicacy that Refen uses when depicting a model slicing their own chest open to remove the toxic pieces of another model they have killed and eaten.

I would disagree with Meades that art which seeks to represent the sublime is not itself sublime. The immersive nature of cinema is ideal for depicting the sublime. Especially science fiction films. Burke defined the sublime’s characteristics as ruggedness, lack of clarity, infinity and darkness. Darkness and the infinite bring to mind the complete darkness and endlessness of space.

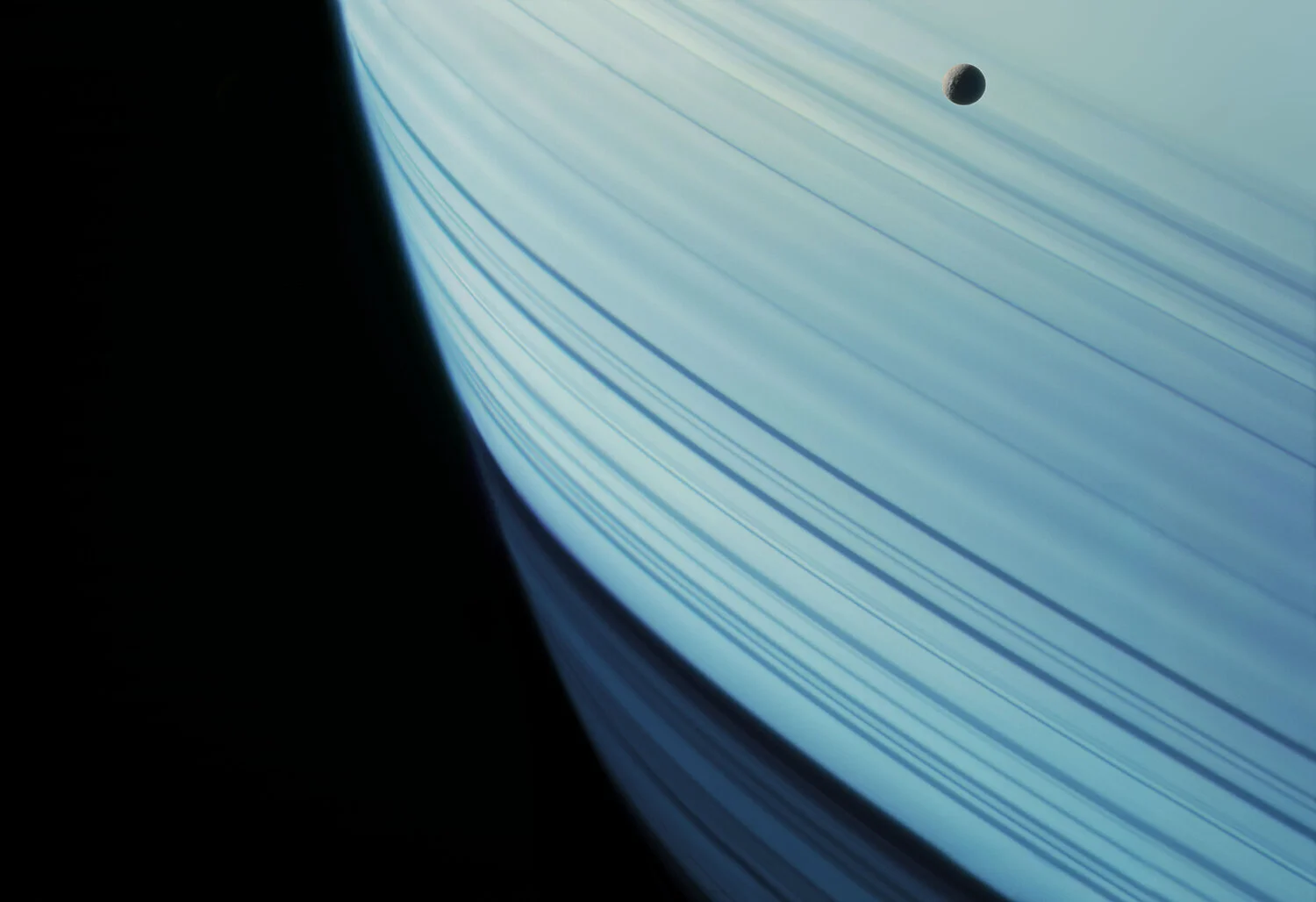

The sublime in space

Many artistic works that attempt to represent space capture this sense of the sublime. The beauty of extraterrestrial phenomenon can be mixed with the terror that comes from their sheer scale of heavenly bodies, the huge power behind the physics that creates and destroys worlds, the apparent lifelessness of the cosmos, the crushing danger of the void and the fear of the unknown that darkness brings.

A good example is the photography of NASA and ESA probes, especially those gathered together for the 2016 Natural History Museum exhibition Otherworlds: Visions of our Solar System, but it can be found in the works of Iain M. Banks and the better episodes of Dr Who.

It is the vastness of space that stirs terror in us, which is ironic because the hard vacuum of space is very dangerous. Alien is scarier than Gravity because the thought of something terrible coming out the darkness is scarier than the idea of an accident in a hostile environment.

Space has the quality of being sublime, partly due to the universe's supreme scale but also because in the mind of science fiction writers it can inspire hope. The hope of a better world just beyond our reach or the hope that a spirit of adventure and discovery can unite people and inspire us to something greater. Hope is the beauty and space itself is the terror.

Nowhere is the hope better summed up than in the spirit of the 1960s space exploration and the utopian science fiction it inspired. Novels such as Frank Herbert’s Dune showed the possibilities of space and how dangerous other worlds could be. The best example of cinema science fiction from this period that captures the sublime in space is Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The film was made during the height of the Cold War. Kubrick began work on it in 1964, just two years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the world had been a hair’s breadth away from complete annihilation by new technological marvels of unparalleled destructive power. Meades also identified the sublime with the explosion of atomic bombs. The fear of nuclear war mixed with the sheer power of modern technology is another way in which 1960s science fiction captures the sublime.

Hope for the future

Hope in 2001 is shown through its optimism about space travel. It was released 14 months before the moon landing and its main theme is the possibility of space travel. Kubrick envisioned the film partly as a presentation about futurism and, in his own words, to: “Inform, intrigue and normalise ideas of technological progress and space travel.”

This film is a study of how people at the time imagined space exploration would progress. Scientists from NASA were invited to submit their ideas of what space travel would be like in 30 years’ time and painstaking detail was taken to be as scientifically accurate as possible. Ironically what the scientists failed to predict was the stagnation in space technology of the following decades.

The year of the film’s title is based on the scientists who advised the film’s belief that there would be a round trip to Mars by the 1980s and that a crewed mission to Jupiter would follow at the turn of the millennium.

The film did not just imagine a bold future for space travel. Companies like IBM contributed speculative designs for the computers of tomorrow, which informed the AI Hal, and Ford supplied the design of a future car that appears in a news clip that is watched during the sequence when Dr Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester) arrives on the moon.

Designers submitted ideas for what men’s clothing would look like in 35 years’ time. According to the film, the future will resemble Edwardian business suits, which keeps the film’s style from dating too obviously. Kubrick said: “The problem is to find something that looks different, and that might reflect new developments in fabrics, but isn’t so far out to be distracting.” Buttons, for example, are not present on the film’s costumes.

Lots of consideration was put into what the ships and space stations would be like or what life on the moon would be like. Beautifully intricate models were made to show the audience the technological possibilities of the near future. Thought was put into very minute detail, such as making accurate animations for the display screens that appear when space ships are coming into dock in the moon arrival sequence or on the display screens that Dr Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Dr Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) observe in the Discovery One.

Fear in space

There are contradictions in what appears at first to be a positive vision of the future in this film. The satellites that are shown orbiting the Earth immediately after the Dawn of Man sequence are military satellites. This creates an obvious parallel between the first weapons we see being used by the apes in the Dawn of Man sequence and their much more powerful descendants orbiting the Earth.

Details from narration that was originally included in the script, but was dropped from the film, said that these were nuclear weapons from all the world’s great powers. It also said that the weapon system was like an airline with a perfect safety record, no one expected it to last forever. The 1960s fear of nuclear annihilation is translated into space.

Despite the militarisation of space, 2001 also depicts American and Russian scientists having a friendly chat on the space station. I prefer this more optimistic vision of people coming together to explore space, which is found in other great works of 1960s science fiction like the original series of Star Trek. The future of 2001 is a little less optimistic, but does mix ideas of unity between nations in the exploration of space and conflict between nations with the weaponisation of space. These two concepts together capture the sense of beautiful hope, but also terrible destruction that make up the sublime.

Sublime alien encounters

2001 best captures the sublime through the humans’ and proto-humans’ encounters with the alien monolith. An object that matches Meades definition of the sublime as being a force beyond mankind’s control and Burke’s definition of something possessing darkness and the infinite. In the final of the film’s four distinct sequences, the monolith is literally a portal to “Beyond the Infinite.”

The mix of beauty and terror that the monolith inspires in the audience can be found in the use of Hungarian composer György Ligeti’s Requiem, a haunting piece of music that has no discernable individual voice, but instead a formless expression that is both beautiful and terrifying.

This music accompanies the scene where Bowman is transported through the monolith. As Bowman travels we see a blur of abstract images that bring to mind paintings of Wassily Kandinsky, whose attempts to express intangible emotions are sublime in themselves.

The sublime and the Kuleshov Effect

The footage of the alien world that Bowman travels over after his transportation is of Scotland and Monument Valley, with the colour of the film adjusted. This brings out feelings of the sublime by taking something that is familiar and juxtaposing it with the abstract images from Bowman’s transportation to give the feeling a strange alien world.

In cinema this is known as the Kuleshov Effect named after Soviet filmmaker Lev Kuleshov, who discovered it. Kuleshov Effect shows that viewers get more information from the interactions of different shots than from individual shots. Complex sensations, such as that of the sublime, can be created through the interactions of footage of different objects.

Thus the combination of footage of ordinary landscapes such Scotland and Monument Valley, with the colour adjusted, can be transformed into bizarre alien worlds that engender sensations of the sublime, via the Kuleshov Effect that occurs when the viewer watches this sequence. The sublime itself is also an emotional Kuleshov Effect as its sensation comes from the juxtaposing of beauty and terror.

Unknowable aliens

The aliens in 2001 are unknowable with their strange landscape and of bizarre structures such as the diamonds that appear floating above the infinite horizon during Bowman’s transportation. The former is reminiscent of way that Turner painted light in his later works and the latter brings to mind the sublime geometric abstractions of Piet Mondrian. Original versions of the script included cities made out geometric shapes that would have given a hint at the architecture of these unknowable aliens.

The film ends with a climax that sums up the sublime with Bowman leaving physical form behind to be reborn as a Starbaby, a creature of pure energy and light. The film ends with the Starbaby floating above the Earth, Bowman having transcended the humanity that that we saw awakened in the Dawn of Man sequence. Older versions of the script, as well as Arthur C Clark’s novelisation of the film, end with the Starbaby simultaneously detonating the nuclear devices that circle the Earth. The sublimity of transcendence and the infinite identified by Burke is linked with the sublimity of nuclear explosions identified by Meades.

Other works of science fiction

No science fiction film so perfectly evokes the wondrous beauty and mind-numbing terror of the great expanse of nothing that lies beyond the heavens as 2001: A Space Odyssey. Other works of science fiction capture the sublime, such as the works of Iain M. Banks, whose novels contain creatures of pure thought and energy who inhabit a plane of existence known as the Sublime.

The writing of NK Jemisin captures the awesome and terrifying power of nature that is associated with the sublime. In her novels, the forces that in our world are beyond human control can be controlled by people, which only makes earthquakes and volcanoes more terrifying when they can be created by human anger or pain.

Ada Palmer’s novels capture the beautiful diversity of humanity and contrast that against the merciless sweeping of time. People are nothing next to the majesty of the philosophies that have shaped the world and they are sublime in their power and how people are consumed by them.

Terry Pratchett made characters of gods and death that were beautifully human whilst still maintaining their awesomeness and their terrible indifference to humanity. He could evoke the sublime and, unusually, combine it with warmth and humour.

Experiencing the sublime

Science fiction as a gene is uniquely suited for depicting the sublime as space is filled with both beauty and terror. Transporting the audience to a world where the wonder and awe of the most powerful forces in the universe can be experienced not only depicts the sublime, but creates feelings of sublimity amongst the viewer.

Both Meades and Burk believed that certain works of art could be sublime of themselves by imbuing the forces that are beyond human understanding or control. They have found the sublime in art forms from painting to architecture. I have sought to make the case that certain works of science fiction should be added to the inventory of the sublime.

It is through creating great works of art that humanity strives to match the awesomeness of nature. Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey is such a work that goes beyond depicting the sublime, but is sublime. It is rare that works of art both reach for something greater than depiction and lets us reach for something greater ourselves, but 2001: A Space Odyssey is such a work of art.